|

Ovarian Cysts

Cysts are fluid filled spaces within the ovary. They are very common, and may be physiological or pathological, benign or malignant. Functional or physiological cysts are either follicular or of corpus luteum origin. Follicular cysts form when a follicle fails to rupture at midcycle, leading to its continuous enlargement. Usually these cysts are asymptomatic and disappear without any intervention within one or two months. Similarly, a persistent corpus luteum may fail to disintegrate before menstruation, and enlarge in size. As well, it gives no symptoms in the majority of cases, though it may lead to some alteration in menstruation. However, both follicular and luteal cysts can become haemorrhagic, if bleeding occured within them, leading to rapid increase in size and severe pain. Otherwise, they may cause pressure symptoms, if they are large in size (>7 cm). Torsion of the whole ovary carrying the cyst may compromise blood flow, leading to severe pain. Immediate surgical intervention will be indicated in such cases.

Certain women are more prone to develop such cysts than others. This is especially so after induction of ovulation with clomid (14%), and after using progestogens only pills, injections or implants for contraception. On the other hand, using a combined oral contraceptive pill may reduce the overall risk of developing such functional cysts by preventing ovulation. This may not be true for the newer pills with low hormone concentration.

Different characteristics are used to differentiate benign from malignant cysts, but the final diagnosis should always be histological. It is important to take the sonographic picture within a clinical context to narrow the spectrum of the diagnostic options. This is especially so as more than 30 different ovarian tumours subypes have been recognised, and there are no corresponding diagnostic ultrasound parameters to match them. The clinical factors to be taken into consideration should include the patient's age, presenting sympotms, personal and family history of ovarian, breast or colon cancers.

Despite these restrictions certain ovarian cysts / masses have characteristics ultrasonic pictures which make the diagnosis most probable. Examples of such tumours include:

Simple cysts

Simple cysts are commonly characterised by:

|

|

|

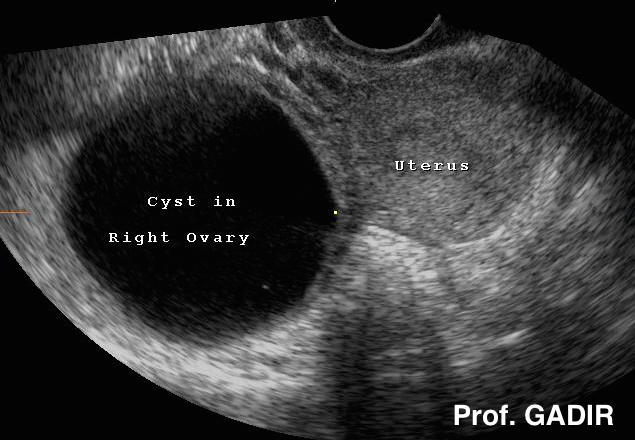

A simple ovarian cyst on the right side of the uterus fulfilling all the characteristics mentioned before |

Other commonly seen benign cysts are haemorrhagic cysts, endometriomas and dermoid cysts.

Haemorrhagic ovarian cysts

Bleeding may occur within the confines of any simple or complex ovarian cyst. The ensuing haemorrhagic cyst may show the following patterns on transvaginal scan examination:

-

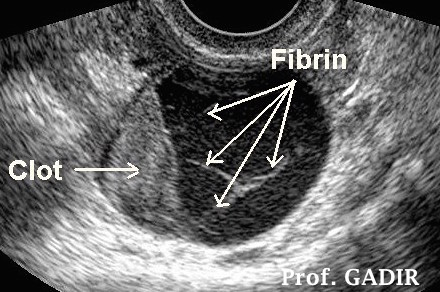

A reticular pattern formed by fibrin deposits is the most common appearance of haemorrhagic cysts. It may simulate the presence of septa, but as they are made of fibrin they may show no vascular markings on colour Doppler mapping. This pattern could be mistaken for mucinous cyst-adenomas.

-

The second most common appearance is a retracted triangular or curvilinear clot with the rest of the cyst being anechoic reflecting the sequestered serum. It could be mistaken for a papillary cystadenoma with a neoplastic mural nodule.

-

A bright or echogenic solid look of a fresh blood clot could be seen when scanning is done within a short time after bleeding. This pattern on the other hand could look like a solid ovarian mass.

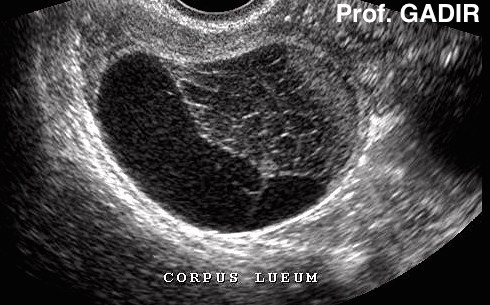

The most common haemorrhagic cyst is the corpus luteum. Because of the variety of its imaging appearances it could be mistaken for endometriomas, serous and mucinous cystadenomas and dermoid cysts. A corpus luteum usually changes texture and disappears within a short period of time while other pathological cysts maintain their shape and texture on repeated examinations.

A haemorrhagic cysts could be a chance finding during transvaginal scan examination but pelvic pain is the most common presentation. This is usually midcycle lower abdominal pain after ovulation. It could be due to stretching of the ovarian capsule by the increase in cyst size by blood, leakage of blood into the pelvis causing peritoneal irritation or partial twisting and untwisting of the enlarged ovary. The cyst could attain a large size and free echogenic fluid could be seen in the pelvis during transvaginal scan examination. It should not be mixed up with an ectopic pregnancy which could give similar ultrasound findings. In this case a positive pregnancy test and a short period of amenorrhoea would be useful clues.

|

|

A haemorrhagic cyst [corpus luteum] with a large blood clot occupying most of the cyst. Haemolysis started at the periphery as shown by dark areas of sequestered serum.

|

|

|

Haemorrhagic cyst [corpus luteum] with a retracted blood clot and fibrin trabeculae shown as bright strands within the sequested serum

|

|

|

A haemorrhagic cyst [corpus luteum] with a retracted blood clot showing retricular inner pattern within the clot indicating haemolysis of the red blood cells.

|

|

|

|

An endometrioma which looks like a haemorrhagic cyst. The fluid level is made by a retracted blood clot or debris on one side and free serum on the other side

|

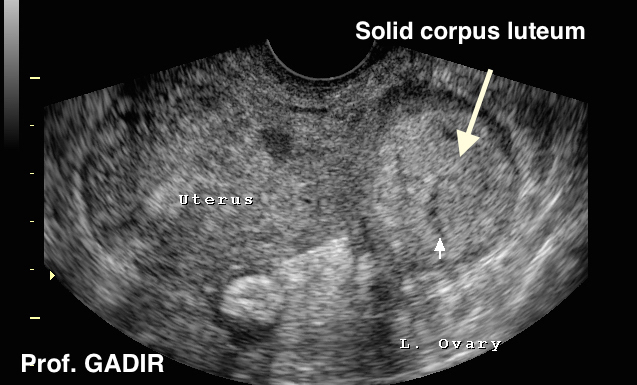

Occasionally a corpus luteum may have a solid texture as shown

by the neighbouring image

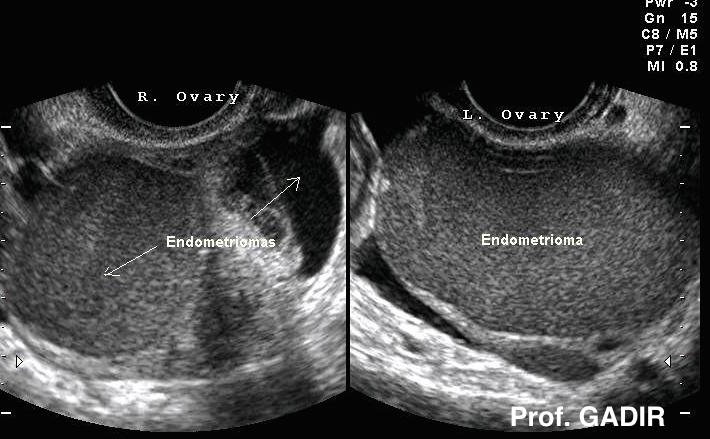

Endometriomas

Vaginal scanning could show an endometriotic cyst in one or both ovaries as cystic mass with thick wall, homogeneous low level internal echoes and occasionally wall calcifications. However this pattern is seen in other adnexal masses including dermoid and haemorrhagic cysts, tubo-ovarian abscess and ectopic pregnancies. Furthermore purely cystic or cysts with some internal debris or septae and solid-looking appearances have been described in histologically proven cases of endometriosis. This was thought to be due to the natural course of endometriomas which resembles the natural resolution course of any other haematoma.

It is important to remember that only 15-20% of women with endometriosis have ovarian endometriomas. Accordingly a diagnosis of endometriosis could not be excluded by the mere absence of ultrasonically visible ovarian involvement.

|

Bilateral endometriomas showing the most

common texture. Note the crescent shaped

normal ovarian tissue at the periphery.

Different textures are also common, as

shown by the 3 images below |

The 3 images shown below reveal a different texture for different histologically confirmed endometriomas in different patients. Colour was used to enhance these differences. The first picture showed a fluid level occasionally seen in haemorrhagic cysts. Accordingly there is no appearance exclusively specific to an endometrioma and the clinical picture would help in the final interpretation of the result. This confirms the importance of pelvic scanning being conducted by gynaecologists who could use the scan probe to extend their clinical judgement for the benefit of that particular case. It could also be used to elicit site specific tenderness and to test for pelvic adhesions.

Normally pelvic organs move freely against each other and relative to the pelvic sidewall. This normal ‘sliding sign’ could not be elicited when organs are stuck together with adhesions. However transvaginal scan or even MRI examinations might show no abnormality. This is especially so when only pelvic sidewall implants are present without any significant ovarian involvement..

Paraovarian cysts

Occasionally, cystic masses may be seen in the pelvis. It may be difficult to decide whether such a cystic mass rises from one ovary or the other. In such cases clinicians may resort to MRI to verify the nature of such cystic masses. It is important to keep paraovarian cysts in mind when seeing such extra ovarian cysts. They can attain very large size, but usually have simple cyst characteristics.

The above two ultrasound and laparoscopic images show a right paraovarian cyst with a neighbouring right cystic ovary.The patient presented with recurrent episodes of subacute right side pelvic pain, mostly due to intermittent torsion episodes of this cyst. Her symptoms totally resolved once the cyst was removed laparoscopically.

Dermoid Cysts

Dermoid cysts or cystic teratomas are the most common benign cysts in young women. They contain all cell types in the body except gonadal tissue. They constitute up to 25% of all ovarian neoplasm and could be bilateral in 15-20% of cases. The risk of malignant transformation is 1-3%. They are often diagnosed incidentally during pelvic scan examinations but could present with pain or pressure symptoms. Occasionally they might produce different chemicals and hormones which could dictate their presentation mode. They could show different echo-patterns during transvaginal scanning which is a reflection of the different types of tissues they harbour. The inner layer might have single or multiple protuberances (Rokitansky) containing bone, teeth or hair which are strong reflectors of ultrasound causing distal shadowing. Highly differentiated monodermal teratomas could be seen. A good example is the epidermoid mass with an inner lining entirely composed of stratified squamous epithelial cells with no evidence of any hair, bone or a Rokitansky tubercle. Hyper-reflective keratin would be the imposing texture on transvaginal scan examination. However the most frequent finding is the presence of hair strands which gives a characteristic ultrasound pattern. All these characteristics could be summarised into the following patterns which could be suggestive of the diagnosis:

-

An echo-poor cystic structure with an echogenic mass inside

-

Echogenic particles within a low echogenicity fluid giving a mesh-like appearance

-

Fat-fluid interface within the cyst.

Dermoid cysts usually grow 1.8 mm in diameter every year in premenopausal women. An increase in size of >2.0 cm every year and a size of >6.0 cm are usually used to indicate surgery because of the known complications of malignancy changes and torsion in such circumstances. On the other hand benign dermoid cysts virtually do no increase in size at all in postmenopausal women.

- The first double ultrasound image above shows a semi solid mass in the right ovary, which proved to be a dermoid cyst. The other ovary was polycystic and harboured a mature follicle.

- The second image showed a dermoid cyst with characteristic echo pattern of hair strands

- The first ultrasound image above shows a small dermoid cyst with distinct fat-fluid interface.

- The second abdominal ultrasound scan shows a cyst with typical hair shadows at the centre, and Rokitansky nodule at the top left corner.

- The first double ultrasound image above shows bilateral dermoid cysts, each of different ultrasound pattern in the same patient.

- The second image shows an epidermoid mass in the left ovary, with echogenic but homogeneous keratin texture. No Rokitansky nodule, bone or hair shadows can be seen. A vascular corpus luteum is seen in the right ovary.

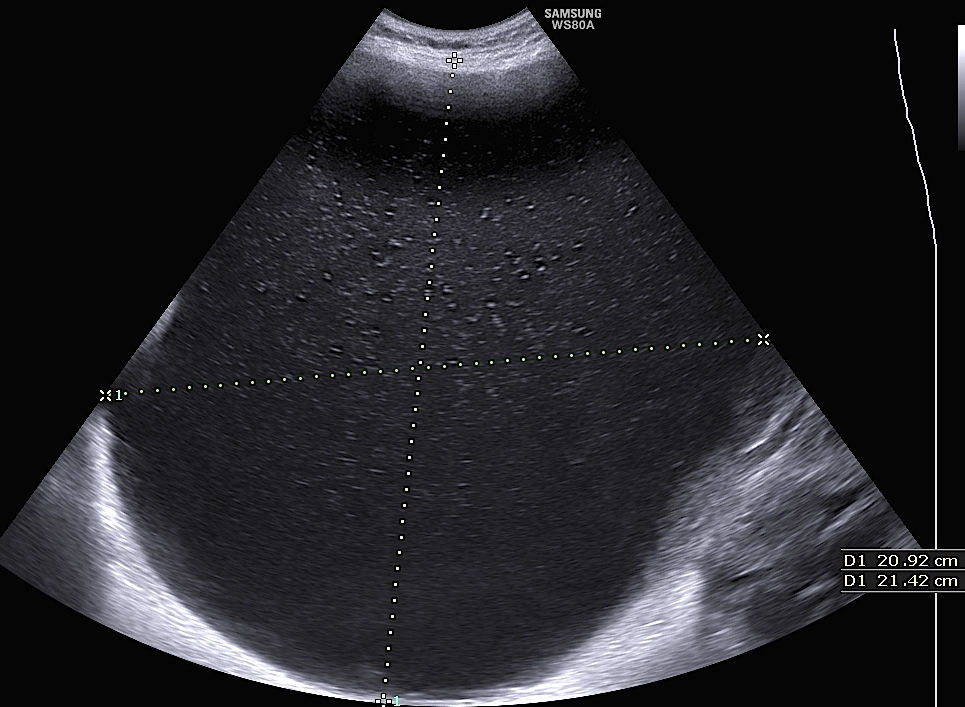

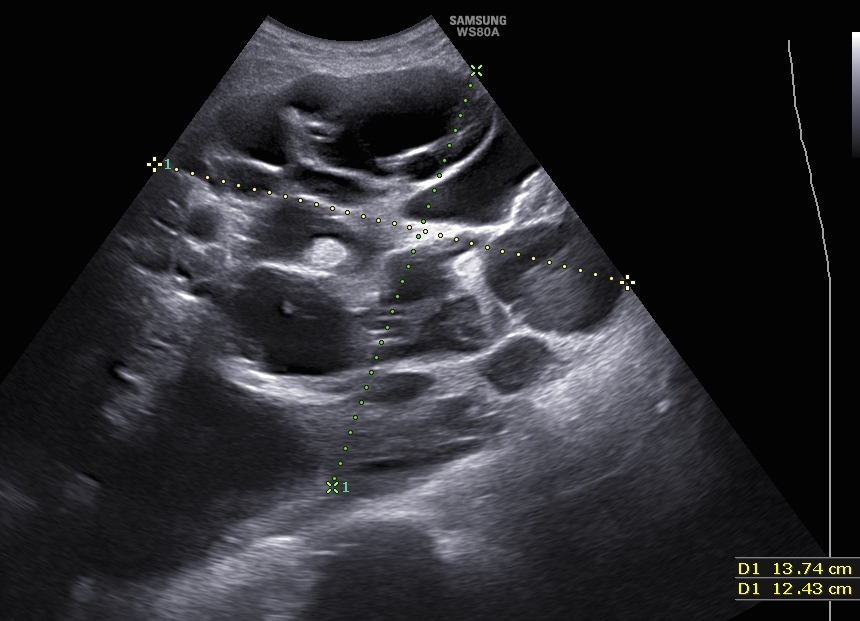

|

|

|

The first ultrasound image above shows a 21 x 20 cm

cyst with thin wall and no septae or solid tissues. It was

part of a large mass with a lower multicystic area 13.7 x

12.4 cm rising from the left ovary, as shown in the

second image above. There was no ascites and colour

Doppler showed very little vascularisation. During

laparotomy, the top cyst yielded 6 litres of fluid. The

mass shown by the neighbouring photograph depicts

the lower multicystic part of the ovarian mass. The

tumour proved to be a mature cystic teratoma, with all

body tissues represented. |

Other benign ovarian cysts

Mucinous cystadenomas make 20% of all benign ovarian tumours and tend to occur more often in middle age women. They could reach large size of 20 - 30 cm before being discovered. Small cysts with different echogenicity could be found along the thickened wall of the large cyst. They are all filled with mucous which has low echogenicity and could show layering with the more reflective layer at the back of the large cyst. As well papillary projections are occasionally found on the inner wall of the larger cyst. In most cysts blood vessels could be seen within the thickened wall making Doppler studies less diagnostic of malignant changes.

Serous cystadenomas make 30% of benign ovarian tumours and are usually much smaller than the mucinous ones. They could be bilateral in up to 30% of the cases. They are multilocular with clear fluid and multiple small papillae projecting into the cyst from the inner cyst wall. Doppler studies usually show no blood flow within the cyst wall but would be of high impedance if at all detectable. They are more liable to change malignant than the mucinous type to form serous adenocarcinoma which make about 70% of all ovarian carcinomas.

Solid ovarian masses

This group include fibromas which are the most common type, granulosa cell tumour and Brenner tumours. They all tend to have the same ultrasound appearance of uniform echotexture which is more echogenic compared to the neighbouring normal ovarian tissues. With granulosa cell tumour the endometrium would show excessive oestrogen stimulation and the patient would give history of recurrent episodes of uterine bleeding.

In young adolescent girls they are most probably germ cell tumours including dysgerminomas, immature teratomas and endometrial sinus tumour. Tumour markers including hCG, alpha fetoprotein and lactate dehydrogenase should be checked. In this young age group unilateral oophorectomy is the most likely line of management with adjuvant chemotherapy.

The first image below shows a solid mass in the right ovary seen as a dark shadow. This is also shown in the second coronal image of the same ovary. The third laparoscopy image showed a winkled hard mass rising form the outer surface of the right ovary. This proved to be spindle cell tumour after histopathological examination. This patient was 32 years old at the time.

Other solid adnexal masses should be kept in mind. The ultrasound image below shows a large solid heterogenous mass initially thought to be either an ovarian fibroma or broad ligament fibroid. 3D rendering revealed the mass to be attached to the right ovary, with no anatomical connection to the uterus. It proved to be a parasitic fibroid attached to the right ovary as seen in the image below. The mass was a coincidental finding in a patient who presented with long-standing secondary amenorrhoea. The mass was removed laparoscopically and the patient resumed menstruating within few weeks. This case was reported in Gynaecological Endocrinology, Feb 2010; 26(2):93-95. 'Secondary amenorrhoea with high inhibin B level caused by parasitic ovarian leiomyoma'

Before moving on from solid ovarian or adnexal masses, it is a right statement to make that all solid or partially solid ovarian masses should be treated surgically especially in postmenopausal women.

Malignant tumours

The life time risk of malignancy is 1.8% which is reduced to 0.8% after using an oral contraceptive pill for 5 years. On the other hand this risk is increased to 6.7% if a first degree relative has already been inflicted and to 40% in families with a genetic syndrome. Other factors including the patient’s age and the size of the cyst should be taken into consideration when making a provisional diagnosis of the nature of an adnexal mass. The life time risk of malignancy at the age of 60-69 years is 12 times more than at the age of 20-29 years. On the size side, masses > 10 cm in diameter are more likely to be malignant.

The ultrasonic characteristic usually seen with ovarian malignancy include:

On the other hand the presence of healthy ovarian tissue on the side of a cyst or a mass [crescent sign] is strongly suggestive of a benign nature. Absence of such a sign has a sensitivity of 96% and specificity of 76% in diagnosing ovarian carcinoma. However, it is not very helpful in differentiating benign from borderline masses.

The importance of these characteristics in differentiating benign from malignant cysts is especially important in 10-15% of postmenopausal women, who still show ovarian cysts at different times. Purely cystic masses less than 5 cm in diameter, with no septate, or solid components are most unlikely to be malignant. With a normal CA 125 test, the patient should be scanned after 3, 6. 9, 12 months, and annually afterwards. Surgical intervention will be indicated, if the patient became symptomatic, or the cyst changed texture or increased in size. On the other hand, a high CA 125 level in a postmenopausal woman with an ovarian mass has a positive predictive value of 70% for diagnosing a malignancy.

It is important to mention that the value of CA125 in the diagnosis of cancer is hampered by the fact that it is a marker of epithelial tumours. Furthermore, it can be increased in many non malignant conditions, including endometriosis and fibroids.

In recent years ultrasound scan examinations by experienced operators have been found to be reliable in the clinical diagnosis of ovarian cancer. In fact, few publications showed that including CA125 in the diagnostic setup reduced the diagnostic sensitivity of the ultrasound scan examination.

Presence of fluid in the pelvis is an important sign to look for, especially in postmenopausal women. Normally little if any fluid may be seen in the pouch of Douglas in postmenopausal women, ranging between <2 ml - 5.5 ml, as reported by different authours. Accordingly, moderate amount of fluid should raise the suspicion of the attending gynaecologist to the possibility of ovarian malignancy, or hepatic disease.

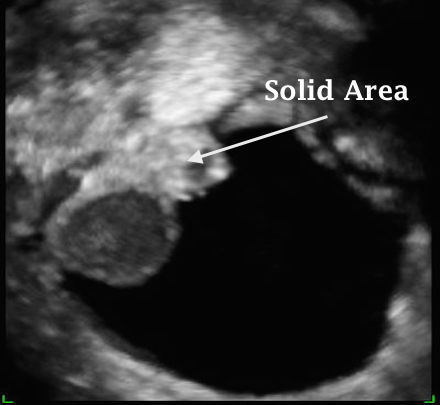

The above two ultrasound images show respectively:

- A large left ovarian cyst with multiple septae seen in a 60 year old patient who presented with postmenopausal bleeding. The cyst proved to be malignant. The complex mass in the right ovary showed solid and cystic areas in the same patient. It also proved to be malignant.

- The second image in a different patient, shows a highly echogenic solid area, flanked by an area of medium echogenicity and two totally anechoic areas.

Though different reliable scoring systems are used to differentiate malignant from benign ovarian cysts and masses, histological diagnosis remains to be the most reliable method.

- The first ultrasound image above shows a unilocular solid cyst, with ground glass fluid appearance, and two solid areas inside. The cyst wall was 1.6 cm thick.

- The second colour Doppler ultrasound image shows axial and sagittal views of the same cyst respectively, with predominantly peripheral vascular channels, without the bizarre pattern commonly seen in malignant tumours.

This mass proved to be an endometrioid carcinoma of the left ovary. The patient was 38 years old, had vague abnominal pains, excessive but regular menstrual loss, no change in body weight and no evidence of ascites.

The neighbouring ultrasound image shows a multicystic solid ovarian mass. There is only one solid area in the cyst, with a second small attached cystic area. There are no septae, and power Doppler mapping showed poor peripheral vascularisation. Histopathological assessment showed a borderline ovarian tumour.

The complementary role of Doppler ultrasound in the diagnosis of ovarian malignancy will be discussed in the Doppler Ultrasound section in this book.

Important Points

Pelvic masses of non-ovarian origin should always be kept in mind. Examples of such lesions include pelvic kidney, broad ligament fibroids, pedunculated uterine fibroids, tubo-ovarian inflammatory lesions and diverticular abscesses.

|